Antarctic ice shelf demise

New research, based largely on information from the Copernicus Sentinel-1 and ESA’s CryoSat satellite missions, has revealed alarming findings about the state of Antarctica’s ice shelves: 40% of these floating shelves have significantly reduced in volume over the past quarter-century. While this underscores the accelerating impacts of climate change on the world’s southernmost continent, the picture of ice deterioration is mixed.

The study, funded by ESA’s Earth Observation Science for Society programme and now published in the journal Science Advances, is based on 100,000 satellite radar images to produce a major assessment of the ‘state of the health’ of Antarctica’s ice shelves.

These massive floating extensions of the continent’s ice sheet play a crucial role in stabilising the region’s glaciers by acting as buttresses, slowing the flow of ice into the ocean.

The Antarctic, therefore, faces a double whammy – as the ice shelves get smaller, the rate of ice lost from the ice sheet increases.

The research team, led by scientists from the University of Leeds, found that 71 of the 162 ice shelves around Antarctica have reduced in volume, releasing almost 67 trillion tonnes of meltwater into the ocean. Apart from the issue of the ice shelves losing mass, this addition of freshwater into the ocean could have implications for ocean circulation patterns.

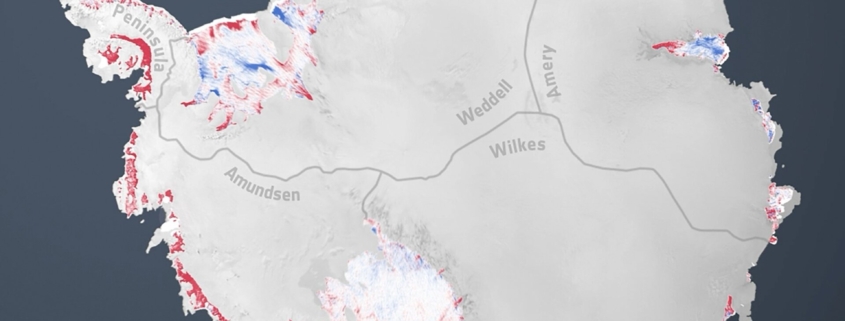

Moreover, the research team found that almost all the ice shelves on the western side of Antarctica experienced ice loss. In contrast, most of the ice shelves on the eastern side remained intact or increased in mass.

Benjamin Davison, a research fellow at the University of Leeds, said, “There is a mixed picture of ice-shelf deterioration, and this is to do with the ocean temperature and ocean currents around Antarctica.

“The western half is exposed to warm water, which can rapidly erode the ice shelves from below, whereas much of East Antarctica is currently protected by a band of cold water at the coast.”

Antarctica is a vast continent, and the seas on the western side experience different currents and winds compared to the east, and this drives warmer water underneath the ice shelves on the western flank.

As a result, the Getz Ice Shelf experienced some of the biggest ice losses, where 1.9 trillion tonnes of ice were lost over the 25-year study period. Just 5% of this was caused by calving, where large chunks of ice breakaway from the shelf and fall into the ocean. The rest was due to melting at the base of the ice shelf.

Similarly, the Pine Island Ice Shelf lost 1.3 trillion tonnes of ice. Around a third of this loss – 450 billion tonnes – was due to calving. The rest was because of melting from the underside of the ice shelf.

In contrast, the Amery Ice Shelf – on the other side of Antarctica and surrounded by much colder waters – gained 1.2 trillion tonnes of ice.

Dr Davison added, “We expected most ice shelves to go through cycles of rapid, but short-lived shrinking, then to regrow slowly. Instead, we see that almost half of them are shrinking with no sign of recovery.”

Anna Hogg, also from the University of Leeds, said, “The study has generated important findings. We tend to think of ice shelves as going through cyclical advances and retreats. Instead, we are seeing a steady attrition owing to melting and calving.

“Many of the ice shelves have deteriorated a lot: 48 lost more than 30% of their initial mass over just 25 years. This is further evidence that Antarctica is changing because the climate is warming.”

Satellites are key to monitoring the remote polar region. Apart from being remote, they are shrouded in darkness during their polar winters.

Here, satellites carrying radar instruments, which can ‘see’ through the dark and provide images and measurements year-round are particularly relevant.

The Copernicus Sentinel-1 mission is Europe’s prime radar mission, providing images no matter whether it is day or night and whatever the weather. ESA’s CryoSat carries a radar altimeter to measure changes in the height of the ice, which are needed to calculate changes in actual ice volume.

Noel Gourmelen, from the University of Edinburgh and Earthwave, noted, “ESA’s CryoSat has also been an incredible tool for monitoring the polar environment.

“Its ability to precisely map the erosion of ice shelves by the ocean below enabled this accurate quantification and partitioning of ice shelf loss, but also revealed fascinating details on how this erosion takes place.”

SA’s Mark Drinkwater said, “Monitoring and tracking climate change across the vast Antarctic continent requires a satellite system that captures data routinely throughout the year.

“The European Copernicus programme’s Sentinel-1 satellite mission has fulfilled this need. Together with the historical data acquired by its ESA predecessors ERS-1, ERS -2 and Envisat, the Sentinel-1 mission has revolutionised our ability to take stock of floating ice shelves, as a bellwether for mass balance and the health of the Antarctic ice sheet.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!