Antarctica is a unique continent in that it does not have a native human population.

Antarctica is the only continent with no permanent human habitation. There are, however, permanent human settlements, where scientists and support staff live for part of the year on a rotating basis.

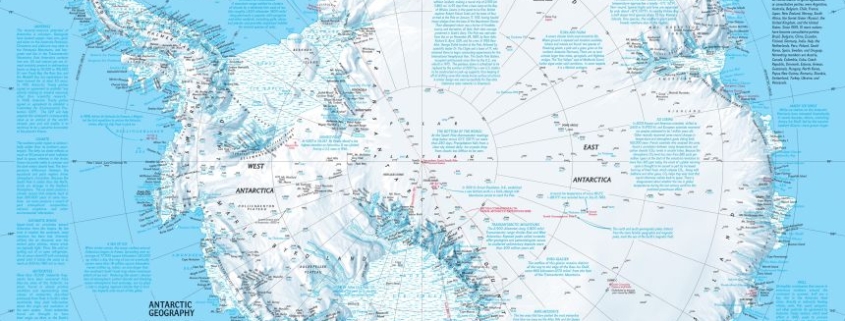

The continent of Antarctica makes up most of the Antarctic region. The Antarctic is a cold, remote area in the Southern Hemisphere encompassed by the Antarctic Convergence. The Antarctic Convergence is an uneven line of latitude where cold, northward-flowing Antarctic waters meet the warmer waters of the world’s oceans. The Antarctic covers approximately 20 percent of the Southern Hemisphere.

Antarctica is the fifth-largest continent in terms of total area. (It is larger than both Oceania and Europe.) Antarctica is a unique continent in that it does not have a native human population. There are no countries in Antarctica. Seven countries made defined claims to Antarctic territory prior to the Antarctic Treaty of 1959. The treaty does not legally recognize any claims.

The Antarctic also includes island territories within the Antarctic Convergence. The islands of the Antarctic region are: South Orkney Islands and South Shetland Islands, claimed by the United Kingdom; South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands, administered by the United Kingdom and claimed by Argentina; Peter I Island and Bouvet Island, claimed by Norway; Heard and McDonald islands, claimed by Australia; and Scott Island and the Balleny Islands, claimed by New Zealand.

Physical Geography

Physical Features

The Antarctic Ice Sheet dominates the region. It is the largest single piece of ice on Earth. This ice sheet even extends beyond the continent when snow and ice are at their most extreme.

The ice surface dramatically grows in size from about three million square kilometers (1.2 million square miles) at the end of summer to about 19 million square kilometers (7.3 million square miles) by winter. Ice sheet growth mainly occurs at the coastal ice shelves, primarily the Ross Ice Shelf and the Ronne Ice Shelf. Ice shelves are floating sheets of ice that are connected to the continent. Glacial ice moves from the continent’s interior to these lower-elevation ice shelves at rates of 10 to 1,000 meters (33 to 32,808 feet) per year.

Antarctica has a number of mountain summits, including the Transantarctic Mountains, which divide the continent into eastern and western regions. A few of these summits reach altitudes of more than 4,500 meters (14,764 feet). The elevation of the Antarctic Ice Sheet itself is about 2,000 meters (6,562 feet) and reaches 4,000 meters (13,123 feet) above sea level near the center of the continent.

Without any ice, Antarctica would emerge as a giant peninsula and archipelago of mountainous islands, known as Lesser Antarctica, and a single large landmass about the size of Australia, known as Greater Antarctica. These regions have different geologies.

Greater Antarctica, or East Antarctica, is composed of older, igneous and metamorphic rocks. Lesser Antarctica, or West Antarctica, is made up of younger, volcanic and sedimentary rock. Lesser Antarctica, in fact, is part of the “Ring of Fire,” a tectonically active area around the Pacific Ocean. Tectonic activity is the interaction of plates on Earth’s crust, often resulting in earthquakes and volcanoes. Mount Erebus, located on Antarctica’s Ross Island, is the southernmost active volcano on Earth.

The majority of the islands and archipelagos of Lesser Antarctica are volcanic and heavily glaciated. They are also home to a number of high mountains.

The oceans surrounding Antarctica provide an important physical component of the Antarctic region. The waters surrounding Antarctica are relatively deep, reaching 4,000 to 5,000 meters (13,123 to 16,404 feet) in depth.

Climate

Antarctica has an extremely cold, dry climate. Winter temperatures along Antarctica’s coast generally range from -10° to -30°C (14° to -22°F). During the summer, coastal areas hover around 0°C (32°F) but can reach temperatures as high as 9°C (48°F).

In the mountainous, interior regions, temperatures are much colder, dropping below -60°C (-76°F) in winter and -20°C (-4°F) in summer. In 1983, Russia’s Vostok Research Station measured the coldest temperature ever recorded on Earth: -89.2°C (-128.6°F). An even lower temperature was measured using satellite data taken in 2010: -93.2°C (-135.8°F)

Precipitation in the Antarctic is hard to measure. It always falls as snow. Antarctica’s interior is believed to receive only 50 to 100 millimeters (two to four inches) of water (in the form of snow) every year. The Antarctic desert is one of the driest deserts in the world.

The Antarctic region has an important role in global climate processes. It is an integral part of Earth’s heat balance. The heat balance, also called the energy balance, is the relationship between the amount of solar heat absorbed by Earth’s atmosphere and the amount of heat reflected back into space.

Antarctica has a larger role than most continents in maintaining Earth’s heat balance. Ice is more reflective than land or water surfaces. The massive Antarctic Ice Sheet reflects a large amount of solar radiation away from Earth’s surface. As global ice cover (ice sheets and glaciers) decreases, the reflectivity of Earth’s surface also decreases. This allows more incoming solar radiation to be absorbed by Earth’s surface, causing an unequal heat balance linked to global warming, the current period of climate change.

Interestingly, NASA scientists have found that climate change has actually caused more ice to form in some parts of Antarctica. They say this is happening because of new climate patterns caused by climate change. These patterns create a strong wind pattern called the “polar vortex.” Polar vortex winds lower temperatures in the Antarctic and have been building in strength in recent decades—as much as 15 percent since 1980. This effect is not seen throughout the Antarctic, however, and some parts are experiencing ice melt.

The waters surrounding Antarctica are a key part of the “ocean conveyor belt,” a global system in which water circulates around the globe based on density and on currents. The cold waters surrounding Antarctica, known as the Antarctic Bottom Water, are so dense that they push against the ocean floor. The Antarctic Bottom Water causes warmer waters to rise, or upwell.

Antarctic upwelling is so strong that it helps move water around the entire planet. This movement is aided by strong winds that circumnavigate Antarctica. Without the aid of the oceans around Antarctica, Earth’s waters would not circulate in a balanced and efficient manner.

Flora and Fauna

Lichens, mosses, and terrestrial algae are among the few species of vegetation that grow in Antarctica. More of this vegetation grows in the northern and coastal regions of Antarctica, while the interior has little if any vegetation.

The ocean, however, teems with fish and other marine life. In fact, the waters surrounding Antarctica are among the most diverse on the planet. Upwelling allows phytoplankton and algae to flourish. Thousands of species, such as krill, feed on the plankton. Fish and a large variety of marine mammals thrive in the cold Antarctic waters. Blue (Balaenoptera musculus), fin (Balaenoptera physalus), humpback (Megaptera novaeangliae), right, minke, sei (Balaenoptera borealis), and sperm whales (Physeter macrocephalus) have healthy populations in Antarctica.

One of the apex, or top, predators in Antarctica is the leopard seal (Hydrurga leptonyx). The leopard seal is one of the most aggressive of all marine predators. This three-meter (nine-foot), 400-kilogram (882-pound) animal has unusually long, sharp teeth, which it uses to tear into prey such as penguins and fish.

The most familiar animal of Antarctica is probably the penguin. They have adapted to the cold, coastal waters. Their wings serve as flippers as they “fly” through the water in search of prey such as squid and fish. Their feathers retain a layer of air, helping them keep warm in the freezing water.

Cultural Geography

A Culture of Science

While the Antarctic does not have permanent human residents, the region is a busy outpost for a variety of research scientists. These scientists work at government-supported research stations and come from dozens of different countries. The number of scientists conducting research varies throughout the year, from about 1,000 in winter to around 5,000 in summer.

Researchers from a variety of scientific backgrounds study the Antarctic not only as a unique environment, but also as an indicator of broader global processes. Geographers map the surface of the world’s coldest and most isolated continent. Meteorologists study climate patterns, including the “ozone hole” that hovers over the Antarctic. Climatologists track the history of Earth’s climate using ice cores from Antarctica’s pristine ice sheet. Marine biologists study the behavior of whales, seals, and squid. Astronomers make observations from Antarctica’s interior because it offers the clearest view of space from Earth.

Even astrobiologists, who study the possibility of life outside Earth’s atmosphere, study materials found in the Antarctic. In 1984, a meteorite from Mars was found in Antarctica. The markings on this meteorite were similar to markings left by bacteria on Earth. If this meteorite, millions of years old, actually has the remains of martian bacteria, it would be the only scientific evidence for life outside Earth.

Daily Life at Antarctica’s Research Stations

Antarctica is a unique cultural place that is best defined by daily life at its diverse research stations. McMurdo Station is a U.S. research center on the southern tip of Ross Island, a territory claimed by New Zealand. McMurdo is the largest station in Antarctica, capable of supporting 1,250 residents. Most of these residents are not scientists, but work to support station operations, construction, maintenance, and daily life. McMurdo has more than 80 buildings and operates like a small city. It has world-class laboratory and research facilities but also a firehouse, dormitories, stores, and the continent’s only ATM.

Like all Antarctic research stations, McMurdo has a specific method of receiving necessary supplies. Once a year, cargo ships bring more than fiv million kilograms (11 million pounds) of equipment and supplies, ranging from trucks and tractors to dry and frozen foods, to scientific instruments. These cargo ships can only reach Winter Quarters Bay, McMurdo’s harbor, during summer, when the pack ice can be breached by U.S. Coast Guard icebreakers. Additional supplies and personnel are flown in from Christchurch, New Zealand, when weather permits.

Base Esperanza, Argentina’s largest Antarctic facility, is located in Hope Bay on the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula. The station is known for a number of Antarctica “firsts.” It is the birthplace of Emilio Marcos Palma, the first person to be born in Antarctica. Base Esperanza also houses the first Catholic chapel (1976) and first school (1978) built on the continent. In 1979, Base Esperanza became the continent’s first shortwave radio broadcaster, connecting the research station with Argentina’s continental territory.

Davis Station is Australia’s busiest scientific research station. It is located in an ice-free area known as the Vestfold Hills. Like most research stations in Antarctica, food is very important at Davis Station. Residents live and work closely together in facilities and outdoor environments that are often very monotonous. As such, food plays an important role in providing variety to residents like those at Davis Station.

Food supplies are, however, very limited. The food supply for a year at Davis Station is rationed, per person per year. Residents live mostly on frozen and canned food. The chef is often thought of as one of the most important people at Davis Station. He or she must make sure to use all commodities in such a way that is both creative and sustainable. Some of the station’s most important events revolve around the chef’s creations, such as the Midwinter Dinner, a traditional, sumptuous feast first celebrated during the 1901-04 British Antarctic Expedition.

Like many of Antarctica’s research facilities, Davis Station has a hydroponic greenhouse. Hydroponics is the practice of growing plants with water and nutrients only. Hydroponics requires excellent gardeners because produce is grown without soil. Fresh produce adds variety and nutrition to Antarctic meals. The greenhouse also serves as a sunroom for sunlight-deprived residents, especially during the long winter months.

Political Geography

Historic Issues

For many European and North American powers, Antarctica represented the last great frontier for human exploration. Fueled by nationalist pride and supported by advances in science and navigation, many explorers took on the “Race for the Antarctic.”

Explorers first skimmed the boundaries of Antarctica on sea voyages. By the early 20th century, explorers started to traverse the interior of Antarctica. The aim of these expeditions was often more competitive than scientific. Explorers wanted to win the “Race to the South Pole” more than understand Antarctica’s environment. Because early explorers confronted extreme obstacles and debilitating conditions, this period of time became known as the “Heroic Age.” Roald Amundsen, Robert Falcon Scott, Edward Adrian Wilson, and Ernest Shackleton all competed in the Race to the South Pole.

In 1911, Amundsen, of Norway, and Scott, of the United Kingdom, began expeditions with the aim of becoming the first man to reach the South Pole. Amundsen’s team set out from the Bay of Whales in the Ross Sea on October 19, while Scott set out from Ross Island on November 1.

Each team used different methods, with drastically different levels of success. Amundsen’s team relied on dog sleds and skiing to reach the pole, covering as much as 64 kilometers (40 miles) per day. Scott’s team, on the other hand, pulled their sleighs by hand, collecting geological samples along the way. Amundsen’s team became the first to reach the South Pole on December 15. The team was healthy, and successfully made the journey out of Antarctica. Scott’s team reached the South Pole on January 17, 1912, suffering from malnutrition, snow blindness, exhaustion, and injury. They all died on their journey home.

Hoping to one-up his predecessors, Shackleton, of the United Kingdom, attempted the first transcontinental crossing of Antarctica in 1914. Shackleton planned the trip by using two ships, the Aurora and the Endurance, at opposite ends of the continent. Aurora would sail to the Ross Sea and deposit supplies. On the opposite side, Endurance would sail through the Weddell Sea to reach the continent. Once there, the team would march to the pole with dog teams, dispose of extra baggage, and use supplies left by Aurora to reach the other end of the continent.

The plan failed. The Endurance became frozen in the pack ice of the Weddell Sea. The pack ice crushed and sunk the ship. Shackleton’s team survived for roughly four months on the ice by setting up makeshift camps. Their food sources were leopard seals, fish, and, ultimately, their sled dogs. Once the ice floe broke, expedition members used lifeboats to reach safer land and were picked up on Elephant Island 22 months after they’d set out on their journey. Although some of the crew sustained injuries, they all survived.

The journey of the Endurance expedition symbolizes the Heroic Age, a time of extreme sacrifice and bravery in the name of exploration and discovery. Apsley George Benet Cherry-Garrard, a polar explorer, summed up the Heroic Age in his book The Worst Journey in the World: “For a joint scientific and geographical piece of organisation, give me Scott; for a Winter Journey, Wilson; for a dash to the Pole and nothing else, Amundsen: and if I am in the devil of a hole and want to get out of it, give me Shackleton every time.”

Contemporary Issues

The second half of the 20th century was a time of drastic change in the Antarctic. This change was initially fueled by the Cold War, a period of time defined by the division between the United States and the Soviet Union, and the threat of nuclear war.

The International Geophysical Year (IGY) of 1957-58 aimed to end Cold War divisions among the scientific community by promoting global scientific exchange. The IGY prompted an intense period of scientific research in the Antarctic. Many countries conducted their first Antarctic explorations and constructed the first research stations on Antarctica. More than 50 Antarctic stations were established for the IGY by just 12 countries: Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Chile, France, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, South Africa, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

In 1959, these countries signed the Antarctic Treaty, which established that: the region south of 60°S latitude remain politically neutral; no nation or group of people can claim any part of the Antarctic as territory; countries cannot use the region for military purposes or to dispose of radioactive waste; and research can only be done for peaceful purposes.

The Antarctic Treaty does support territorial claims made before 1959, by New Zealand, Australia, France, Norway, the United Kingdom, Chile, and Argentina. Under the treaty, the size of these claims cannot be changed and new claims cannot be made. Most importantly, the treaty establishes that any treaty-state has free access to the whole region. As such, research stations supported by a variety of treaty-states have been constructed within each of these territorial claims. Today, 47 states have signed the Antarctic Treaty.

The Antarctic Treaty was an important geopolitical milestone because it was the first arms control agreement established during the Cold War. Along with the IGY, the Antarctic Treaty symbolized global understanding and exchange during a period of intense division and secrecy.

Many important documents have been added to the Antarctic Treaty. Collectively known as the Antarctic Treaty System, they cover such topics as pollution, conservation of animals and other marine life, and protection of natural resources.

The yearly Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting (ATCM) is a forum for the Antarctic Treaty System and its administration. Only 28 of the 47 treaty-states have decision-making powers during these meetings. These include the 12 original signatories of the Antarctic Treaty, along with 16 other countries that have conducted substantial and consistent scientific research there.

Future Issues

Two important and related issues that concern the Antarctic region are climate change and tourism. The ATCM continues to address both issues.

Antarctic tourism has grown substantially in the last decade, with roughly 40,000 visitors coming to the region in 2010. In 2009, the ATCM held meetings in New Zealand to discuss the impact of tourism on the Antarctic environment. Officials worked closely with the International Association of Antarctica Tour Operators (IAATO) to establish better practices that would reduce the carbon footprint and environmental impact of tour ships. These include regulations and restrictions on: numbers of people ashore; planned activities; wildlife watching; pre- and post-visit activity reporting; passenger, crew, and staff briefings; and emergency medical-evacuation plans. The ACTM and IAATO hope more sustainable tourism will reduce the environmental impacts of the sensitive Antarctic ecosystem.

Tourism is one facet of the ACTM’s climate change outline, discussed during meetings in Norway in 2010. Climate change disproportionately affects the Antarctic region, as evidenced by reductions in the size of the Antarctic Ice Sheet and the warming waters off the coast. The ACTM recommended that treaty-states develop energy-efficient practices that reduce the carbon footprint of activities in Antarctica and cut fossil fuel use from research stations, vessels, ground transportation, and aircraft.

The Antarctic has become a symbol of climate change. Scientists and policymakers are focusing on changes in this environmentally sensitive region to push for its protection and the sustainable use of its scientific resources.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!